Damien Rice

Damien Rice | |

|---|---|

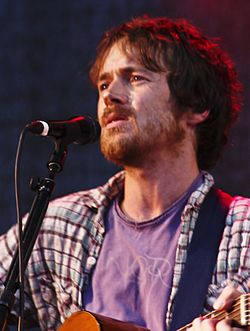

Rice performing in 2010 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 7 December 1973 Dublin, Ireland |

| Origin | Celbridge, Ireland |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1991–present |

| Labels |

|

| Website | damienrice |

Damien George Rice (born 7 December 1973) is an Irish musician, singer and songwriter.[1] He began his career as a member of the 1990s rock group Juniper, who were signed to Polygram Records in 1997. The band enjoyed moderate success in Ireland with two released singles, "The World is Dead" and "Weatherman."[2] After leaving the band in 1998, Rice worked as a farmer in Tuscany and busked throughout Europe before returning to Ireland in 2001 and beginning a solo career. The rest of Juniper went on to perform under the name Bell X1.

In 2002, Rice released his debut album, O. It reached No. 8 on the UK Albums Chart, won the Shortlist Music Prize, and generated three top 30 singles in the UK. He released his second album, 9, in 2006. After eight years of various collaborations, Rice released his third studio album, My Favourite Faded Fantasy, in 2014.[3] He has contributed music to charitable projects such as Songs for Tibet, the Enough Project, and the Freedom Campaign.

Early life

[edit]Rice was born in Dublin on 7 December 1973, the son of George and Maureen Rice. He grew up in Celbridge, County Kildare where he attended Salesian College.[4] He is the second cousin of Irish singer Stevie Mann and English composer David Arnold.[5]

Career

[edit]Juniper

[edit]Rice formed the rock band Juniper along with Paul Noonan, Dominic Philips, David Geraghty and Brian Crosby in 1991. The band met whilst they were schoolmates in Celbridge. After touring throughout Ireland, they released their debut EP Manna in 1995.[6] Based in Straffan, the band continued touring and signed a six-album record deal with PolyGram. Their recording projects generated the singles "Weatherman" and "The World is Dead," which received favourable reviews.[6] They also recorded a song named "Tongue," which was later released on the Bell X1 album Music in Mouth. The song "Volcano" was also written with Juniper but not released. It was later released by both Bell X1, on the album Neither Am I, and on Rice's debut album O.

After achieving some of his musical goals with Juniper, Rice became frustrated with the artistic compromises required by the record label, and he left the band in 1998.[7] He moved to Italy, where he settled in Tuscany and took up farming for a time, then returned to Ireland before busking around Europe.[7] He returned to Italy a second time and gave a demo recording to his second cousin, English composer David Arnold, who then provided him with a mobile recording studio.[5]

Solo career

[edit]

In 2001, Rice's song "The Blower's Daughter" made the top-40 chart.[5] Over the next year, he continued to record his album with guitarist Mark Kelly, New York drummer Tom Osander aka Tomo, Paris pianist Jean Meunier, London producer David Arnold, County Meath vocalist Lisa Hannigan and cellist Vyvienne Long. Rice then embarked on a tour of Ireland with Hannigan, Tomo, Vyvienne, Mark and Dublin bassist Shane Fitzsimons.

In 2002, Rice's debut album O was released in Ireland, the UK and the United States.[8] The album peaked at No. 8 on the UK Albums Chart and remained on the chart for 97 weeks, selling 650,000 copies in the US.[8][9] The album won the Shortlist Music Prize and the songs "Cannonball" and "Volcano" became top 30 hits in the UK.[9][10]

In 2005, Rice participated in the Freedom Campaign, the Burma Campaign UK, and the U.S. Campaign for Burma to free Burmese democracy movement leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[11] He campaigned for her release by writing the song "Unplayed Piano," which he performed at the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize Concert in Oslo.[12][13]

In 2006, Rice released his second album, 9, which was recorded during the two previous years.[14] 2007 was a year of touring, with Rice appearing at England's Glastonbury Festival and the Rock Werchter festival in Belgium[15] In 2008, he contributed the song "Making Noise" for the album Songs for Tibet: The Art of Peace in support of the 14th Dalai Lama and Tibet.[16]

In 2010, Rice contributed the song "Lonely Soldier" to the Enough Project[17] and played at the Iceland Inspires concert held in Hljómskálagarðurinn near Reykjavík centrum.[18] Records released in the UK, Europe and other countries were published by 14th Floor Records via Warner Music.[19] In spring 2011, Rice featured on the debut album by French actress and singer Melanie Laurent. He appears on two tracks on her debut album En t'attendant while collaborating on a total of five tracks which feature on the album.[20] In May 2013, Rice told the audience at the South Korea Seoul Jazz Festival 2013 that he was working on a new album.[21]

On 4 September 2014, Rice's official Twitter account announced his third album, My Favourite Faded Fantasy, to be released on 31 October. On his official website, the date given for the official release was 3 November 2014.[22] The album, featuring the first single "I Don't Want To Change You," was released worldwide on 10 November 2014 to critical acclaim from NPR's Robin Hilton and the London Evening Standard.[23]

In 2020, Rice covered Sia's "Chandelier," with his cover appearing on the Songs for Australia benefit album.

While performing in Valencia, Spain, in late July 2023, Rice found out that Sinéad O'Connor had died when the audience shouted it at him during the show. After taking a moment to process the news, Rice played "Nothing Compares 2 U" as a tribute to O'Connor.[24]

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- O (2002)

- 9 (2006)

- My Favourite Faded Fantasy (2014)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ross, Alex (29 October 2021). "Ed Sheeran confirms his next album is ready to drop 🙌". KISS. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

fellow singer-songwriter Damien Rice had been a huge inspiration

- ^ "Damien Rice". Spotify. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "iTunes Store (pre-order)". iTunes Store. Archived from the original on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "FAQ – Where was Damien born and where did he grow up?". DamienRice.com. n.d. Archived from the original on 2 May 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ a b c "Damien Rice – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ a b "Should We Talk About The Weather?". Hot Press. Retrieved 12 September 2009. (Fee for article)

- ^ a b "The story of O". Yahoo. Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ a b "Official Charts Company for O". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ a b "Damien Rice Readies second album". Billboard. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ "Damien Rice singles placement". irishcharts.ie. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- ^ "Aung San Suu Kyi the world's only imprisoned Nobel Peace Prize recipient". The Burma Campaign UK. n.d. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ "Damien Rice releases new single in support of Aung San Suu Kyi". Burma Campaign UK. 10 May 2005. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ Newsdesk, The Hot Press. "Damien Rice participates in Nobel Peace Prize ceremony". Hotpress. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ^ "9 – Release info". DamienRice.com. n.d. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ^ "Damien Rice's 2007 Concert History". Concert Archives. 15 October 2023. Archived from the original on 15 October 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ^ E-Online (22 July 2008) Sting, Matthews, Mayer Gamer for Tibet Than Beijing Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Raise Hope for Congo". Raisehopeforcongomusic.org. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Inspired By Iceland". Inspired By Iceland. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "FAQ at". Damienrice.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Music". Damien Rice. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "New Album Confirmation". 18 May 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Album information". Damienrice.com/. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Smyth, David (12 September 2014). "Exclusive first listen of Damien Rice's new album My Favourite Faded". The Standard. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ Ezequiel Frontera (27 July 2023). "Damien Rice finds out about Sinead O'Connor's death during a concert in Valencia and sings NC2U". Retrieved 13 August 2023 – via YouTube.

External links

[edit]- Damien Rice – Official website

- Damien Rice – Official MySpace page

- 1973 births

- Living people

- Irish buskers

- Irish folk singers

- Irish pop singers

- Irish male singer-songwriters

- Irish singer-songwriters

- Musicians from County Kildare

- People from Celbridge

- Singers from Dublin (city)

- Winners of the Shortlist Music Prize

- Irish expatriates in England

- Irish expatriates in Italy

- Irish male guitarists

- Indie folk musicians

- 21st-century Irish male singers

- 14th Floor Records artists

- 20th-century Irish male singers

- 20th-century Irish guitarists

- 21st-century Irish guitarists

- 1990s in Irish music

- 2000s in Irish music

- 2010s in Irish music

- 2020s in Irish music