Vorticism

Vorticism was a London-based modernist art movement formed in 1914 by the writer and artist Wyndham Lewis. The movement was partially inspired by Cubism and was introduced to the public by means of the publication of the Vorticist manifesto in Blast magazine. Familiar forms of representational art were rejected in favour of a geometric style that tended towards a hard-edged abstraction. Lewis proved unable to harness the talents of his disparate group of avant-garde artists; however, for a brief period Vorticism proved to be an exciting intervention and an artistic riposte to Marinetti's Futurism and the Post-Impressionism of Roger Fry's Omega Workshops.[1]

Vorticist paintings emphasised 'modern life' as an array of bold lines and harsh colours drawing the viewer's eye into the centre of the canvas and vorticist sculpture created energy and intensity through 'direct carving'.[2]

Prelude to Vorticism

[edit]

In the summer of 1913 Roger Fry, with Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, set up the Omega Workshops in Fitzrovia – in the heart of bohemian London. Fry was an advocate of an increasingly abstract art and design practice, and the studio/gallery/retail outlet allowed him to employ and support artists in sympathy with this approach, such as Wyndham Lewis, Frederick Etchells, Cuthbert Hamilton and Edward Wadsworth. Lewis had made an impact at the Allied Artists' Salon the previous year with a huge virtually abstract work, Kermesse (now lost),[3] and in the same year he had worked with the American sculptor Jacob Epstein on the decoration of Madame Strindberg's notorious cabaret theatre club The Cave of the Golden Calf.

Lewis and his Omega Workshop colleagues Etchells, Hamilton and Wadsworth exhibited together later in the year at Brighton with Epstein and David Bomberg.[4] Lewis curated the exhibition's 'Cubist Room' and provided a written introduction in which he attempted to cohere the various strands of abstraction on display: 'These painters are not accidently [sic?] associated here, but form a vertiginous, but not exotic, island in the placid and respectable archipelago of English Art.'[5]

Rebel artists

[edit]

A quarrel with Roger Fry provided Lewis with a pretext to leave the Omega Workshops and set up a rival organisation.[6] Financed by Lewis's painter friend Kate Lechmere, the Rebel Art Centre was established in March 1914 at 38 Great Ormond Street.[7] It was to be a platform for the art and ideas of Lewis's circle, and a lecture series included talks by Lewis's friend the poet Ezra Pound, the novelist Ford Madox Hueffer (later Ford Madox Ford) and the Italian 'Futurist', Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti had been a familiar – and provocative – presence in London since 1910, and Lewis had seen him create an art movement on the basis of his 'Futurist' manifesto. It seemed as if everything novel or shocking in London was now being described as 'Futurist' – including the work of the English Cubists.[8]

When Marinetti and the English Futurist C. R. W. Nevinson published a manifesto of 'Vital English Art',[9] giving the Rebel Art Centre as an address, it seemed like an attempted takeover. A few weeks later, Lewis took out an advertisement in The Spectator to announce the publication of 'The Manifesto of the Vorticists' – an English abstract art movement that was a 'parallel movement to Cubism and Expressionism' and would, the advertisement promised, be a 'Death Blow to Impressionism and Futurism'.[10]

Inventing Vorticism

[edit]

Ezra Pound had introduced the concept of 'the vortex' in relation to modernist poetry and art early on in 1914.[11] At its most obvious, for example, London could be seen to be a 'vortex' of intellectual and artistic activity. However, for Pound there was a more specific – if obscure – meaning: '[The vortex was] that point in the cyclone where energy cuts into space and imparts form to it ... the pattern of angles and geometric lines which is formed by our vortex in the existing chaos.'[12] Lewis saw the potential of 'Vorticism' as an exciting rallying call that was also sufficiently vague, he hoped, to embrace the individualism of the rebel artists.

Lewis's Vorticist manifesto was to be published in a new literary and art journal, BLAST – ironically, the journal's title had been suggested by Nevinson, who was now persona non grata since the 'Vital English Art' manifesto. The French sculptor, painter and anarchist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska had met Ezra Pound in July 1913,[13] and their ideas on 'The New Sculpture'[14] developed into a theory of Vorticist sculpture. Two artists, Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr, who had turned to 'cubist works' in 1913, joined the rebels – and, although they were not regarded highly by the men, Brigid Peppin argues that Saunders's 'juxtapositions of strong and unexpected colour' may have influenced Lewis's later use of forceful colour.[15]

Another up-and-coming 'English Cubist' using bold, discordant colour combinations was William Roberts. Writing much later, he recalled Lewis borrowing two paintings – Religion and Dancers – to hang at the Rebel Art Centre.[16]

BLAST

[edit]

Although the Rebel Art Centre was short-lived,[17] 'Vorticism' was given assured longevity through the dazzling typography and the audacious (and humorous) 'blasting' and 'blessing' of myriad sacred cows of English and American culture that appeared in the first issue of BLAST: The Review of the Great English Vortex, published in July 1914.

BLAST was launched at a 'riotous celebratory dinner'[18] at the Dieudonné Hotel in the St James's area of London on 15 July 1914.[19] The magazine was mainly the work of Lewis, but also included extensive written pieces by Ford Madox Hueffer and Rebecca West, as well as poetry by Pound, articles by Gaudier-Brzeska and Wadsworth, and reproductions of paintings by Lewis, Wadsworth, Etchells, Roberts, Epstein, Gaudier-Brzeska and Hamilton.[20] The manifesto was apparently 'signed' by eleven signatories.[21] Lewis, Pound and Gaudier-Brzeska were at the intellectual heart of the project, but Roberts's later comments suggest that most of the group were not made aware of the manifesto's contents before publication.[22] Jacob Epstein was presumably too established to be co-opted as a signatory, and David Bomberg had threatened Lewis with legal action if his work was reproduced in BLAST and made his independence very clear through a one-man show at the Chenil Galleries, also in July, where his large abstract painting Mud Bath was prominently displayed outside above the entrance.[23]

Vorticist Exhibition

[edit]

The publication of BLAST could not have come at a worse time, as in August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany. There would be little appetite for avant-garde art at this time of national and international crisis; however, a ‘Vorticist Exhibition’ went ahead at the Doré Galleries in New Bond Street the following year.[24] The forty-nine ‘Vorticist’ works by Dismorr, Etchells, Gaudier-Brzeska, Lewis,[25] Roberts,[26] Saunders[27] and Wadsworth showed a commitment to hard-edged, highly coloured, near-abstract work. Perhaps by way of contrast (or comparison), Lewis also invited other artists including Bomberg and Nevinson to participate.[28]

A catalogue foreword by Lewis clarified that ‘by Vorticism we mean (a) ACTIVITY as opposed to the tasteful PASSIVITY of Picasso (b) SIGNIFICANCE as opposed to the dull anecdotal character to which the Naturalist is condemned (c) ESSENTIAL MOVEMENT and ACTIVITY (such as the energy of the mind) as opposed to the imitative cinematography, the fuss and hysterics of the Futurists.’[29] The exhibition was largely ignored by the press, and the reviews that did appear were damning.[30]

BLAST: War Number

[edit]Just before the exhibition opening, news reached London of Gaudier-Brzeska's death in the trenches in France.[31] A ‘Notice to Public’ in the second number of BLAST explained that the publication had been delayed ‘due to the War chiefly’ and to ‘the illness of the Editor at the time it should have appeared and before’,[32] and the delay allowed the last-minute inclusion of a tribute to the artist.

Compared with BLAST No. 1 this was a scaled-back production – 102 pages, rather than the 158 pages of the first issue and with simple black-and-white ‘line block’ illustrations. However, compared with BLAST No. 1, that did have the advantage of providing ‘a cohesive Vorticist aesthetic’.[33] Jessica Dismorr and Dorothy Shakespear (Ezra Pound's wife) joined a slightly broader range of artists that also included Jacob Kramer and Nevinson. Lewis's rhetoric was more cautious this time – trying to avoid being seen by the readership as unpatriotic. Understandably, he tried to strike an optimist tone with regard to the future of Vorticism and BLAST; however, within a year most of the artists had enlisted or volunteered in the armed forces: Lewis – Royal Garrison Artillery; Roberts – Royal Field Artillery; Wadsworth – British Naval Intelligence; Bomberg – Royal Engineers; Dismorr – Voluntary Air Detachment; and Saunders – government office work.[34]

Vorticists at the Penguin Club

[edit]Ezra Pound had been championing Wyndham Lewis's work from 1915 with a successful New York lawyer and art collector, John Quinn.[35] Relying on Pound's recommendations, a New York Vorticist exhibition was built around forty-six works by Lewis – some already in Quinn's collection – with additional work by Etchells, Roberts, Dismorr, Saunders and Wadsworth. The exhibition was to be at an artist-run establishment, the Penguin Club in New York.[36] Pound arranged for the transportation of works across the Atlantic, and Quinn took on the entire exhibition costs.[37] Quinn had already selected works that he was interested in buying, but after the exhibition, as no works had sold, he eventually purchased most of the larger items.[38]

War artists

[edit]

There was almost no opportunity for the rebel artists to work creatively while on active service.[39] However, Wadsworth, unexpectedly, was able to pursue his artistic interests through the supervision of the dazzle camouflage being applied to over two thousand ships, largely at Bristol and Liverpool.[40]

Towards the end of the war the journalist Paul Konody, now art adviser to the Canadian War Memorials Fund (and someone who had been blatantly anti-Vorticism), commissioned Lewis, Wadsworth, Nevinson, Roberts, Paul Nash and Bomberg to produce monumental canvases on subjects relating to the Canadian war experience for a projected memorial hall in Ottawa. The artists were warned that only 'representative' work would be acceptable, and indeed Bomberg's first version of his Sappers at Work[41] was rejected as being 'too cubist'. Despite these restrictions, the extraordinary canvases feel uncompromisingly modernist, and certainly drew from pre-war avant-garde practices.[42]

Group X

[edit]

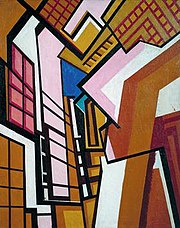

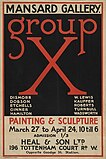

In the post-war years it was difficult for artists to receive patronage and to secure sales. Nevertheless, Lewis, Wadsworth, Roberts and Atkinson all had one-man shows by the early 1920s – each artist navigating his own path between modernism and potentially more saleable recognisable subjects.[43] Lewis organised one more group show, in 1920 at the Mansard Gallery, bringing together ten artists under the banner 'Group X'.[44] Now, however, there was little attempt to unify the artists's contributions beyond Lewis's belief that 'the experiments [by artists] undertaken all over Europe during the last ten years should .... not be lightly abandoned.'[45] The diversity of styles on display, for example, included four self-portraits by Lewis, while Roberts exhibited four quite radical works in his evolving 'Cubist' style.[46] Six of the Group X artists had been in the 'Vorticist' group – Dismorr, Etchells, Hamilton, Lewis, Roberts and Wadsworth – and they were joined by the sculptor Frank Dobson (sculptor), the painter Charles Ginner, the American graphic designer Edward McKnight Kauffer, and the painter John Turnbull. The exhibition was mainly seen as a failure to 'rekindle a flame of adventure'.[47]

Legacy

[edit]The disruption of war and the subsequent mobilisation of the artists contributed to a situation whereby many of the larger Vorticist paintings were lost. An anecdote recorded by Brigid Peppin relates how Helen Saunders's sister used a Vorticist oil to cover her larder floor and '[it was] worn to destruction'[48] – an extreme example of how the paintings were not appreciated. When John Quinn died, in 1927, his collection of Vorticist works was auctioned and dissipated to now untraceable purchasers, presumably in America.[49] Writing in 1974, Richard Cork noted that 'thirty-eight of the forty-nine works displayed by the full members of the movement at the 1915 Vorticist Exhibition are now missing.'[50]

Despite a resurgence of abstract art in Britain in the middle years of the twentieth century, the contribution of Vorticism was largely forgotten until a spat between John Rothenstein of the Tate Gallery and William Roberts blew up in the press. Rothenstein's 1956 Tate Gallery exhibition 'Wyndham Lewis and Vorticism' was actually a Lewis retrospective with very few Vorticist works. And the inclusion of work by Bomberg, Roberts, Wadsworth, Nevinson, Dobson, Kramer under the heading 'Other Vorticists' – together with Lewis's assertion that 'Vorticism, in fact, was what I, personally, did, and said, at a certain period' – incensed Roberts as it seemed that he and the others were being set up to be mere disciples of Lewis.[51] The case made by Roberts in the five 'Vorticist Pamphlets' that he published between 1956 and 1958[52] was hampered by the absence of key works, but led to other self-published books by Roberts which included early studies of his abstract work.[53] A broader survey was provided by the d'Offay Couper Gallery's 'Abstract Art in England 1913–1914' exhibition in 1969.[54]

Five years later, the exhibition 'Vorticism and Its Allies' curated by Richard Cork at the Hayward Gallery, London,[55] went further in painstakingly bringing together paintings, drawings, sculpture (including a reconstruction of Epstein's Rock Drill 1913–15), Omega Workshop artefacts, photographs, journals, catalogues, letters and cartoons. Cork also included twenty-five 'Vortographs' from 1917 by the photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn that had been first displayed at the Camera Club in London in 1918.[56]

Recent exhibitions

[edit]More recently, in 2004 in London and Manchester, 'Blasting the Future!: Vorticism in Britain 1910–1920' explored the links between Vorticism and Futurism,[57] and a major exhibition 'The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World' in 2010–11 brought Vorticist work to Italy for the first time and to America for the first time since 1917, as well as appearing in London.[58] The curators, Mark Antliff and Vivien Greene, had also traced some previously lost works (such as three paintings by Helen Saunders) that were included in the exhibition.

Notes

[edit]- ^ For a full account of Vorticism see the introductory essay by Richard Cork in the exhibition catalogue Vorticism and Its Allies (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974), pp. 5–26. A recent and concise definition is available at the Tate's website: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/v/vorticism.

- ^ As opposed to sculpting in wax to produce casts or using mechanised tools to 'translate clay into marble'. Mark Antliff, 'Sculpural Nominalism/Anarchist Vortex: Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Dora Marsden and Ezra Pound', in Mark Antliff and Vivien Greene (eds.), The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World (London: Tate Publishing, 2010), p. 52.

- ^ Clive Bell in The Athenaeum of 27 July 1912 explained that, in order to appreciate this work, visitors 'having shed all irrelevant prejudices in favour of representation will be able to contemplate it as a piece of pure design'.

- ^ ‘The Camden Town Group: An Exhibition of the Work of English Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others’, Public Art Galleries, Brighton, December 1913–January 1914.

- ^ Quoted by Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 12.

- ^ Karin Orchard, '"A Laugh Like a Bomb": The History and Ideas of the Vorticists', in Paul Edwards (ed.), Blast: Vorticism 1914–1918 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p. 15.

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 17.

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 20.

- ^ The Observer, 7 June 1914.

- ^ The Spectator, 13 June 1914.

- ^ Initially in correspondence in late 1913 and then in an informal talk at the Rebel Art Centre in April 1914 (Philip Rylands, 'Introduction', in Antliff & Greene (eds.), The Vorticists, p. 25, n. 33).

- ^ Ezra Pound in a 1915 interview for the Russian journal Strelets, quoted in Rylands, 'Introduction', p. 23.

- ^ Mark Antliff, 'Sculptural Nominalism/Anarchist Vortex', in Antliff & Greene (eds.), The Vorticists, p. 47.

- ^ Published in The Egoist, 16 February 1914, pp. 67–8, and 16 March 1914, pp. 117–18.

- ^ Brigid Peppin, 'Women That a Movement Forgot', Tate, Etc. 22 (summer 2011), p. 35.

- ^ William Roberts, Some Early Abstract and Cubist Work 1913–1920 (London, 1957), p. 9. Reproductions of these paintings were included in the first issue of BLAST.

- ^ It closed later in 1914 following paranoia, jealousy and squabbling especially with regard to the relationship between Kate Latchmere and Wyndham Lewis and T. E. Hulme – see, Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 17.

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 21.

- ^ The Dieudonné (the 'God-Given') was a French-run hotel at 9–11 Ryder Street (now part of Christie's building in King Street). It closed later in 1914. In William Roberts's large painting from 1961–2 The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, Spring 1915, Roberts represents the BLAST launch as being at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street, Fitzrovia. Richard Cork clarifies that the painting is an 'imaginative evocation' of the event 'rather than a historically accurate record ... . [however] the Tour Eiffel's genial proprietor, Rudolphe Stulik, was always lavish with his hospitality towards the Vorticists; and Roberts ... . testified that "in my memory la cuisine Française and Vorticism are indissolubly linked”' – Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, pp. 106–7.

- ^ BLAST can be viewed online from many sources, including https://library.brown.edu/pdfs/1143209523824858.pdf.

- ^ Under 'Signatures for Manifesto' on page 43 of BLAST No.1 were listed 'R. Aldington', 'Arbuthnot', 'L. Atkinson', 'Gaudier Brzeska', 'J. Dismorr', 'C. Hamilton', 'E. Pound', 'W. Roberts', 'H. Sanders' (sic), 'E. Wadsworth' and 'Wyndham Lewis'.

- ^ Roberts, Some Early Abstract and Cubist Work, p. 9.

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 24.

- ^ Opened 10 June 1915.

- ^ One of the few surviving paintings from this exhibition is Wyndham Lewis's Workshop c.1914–15 in the Tate collection.

- ^ Study for William Roberts's Two Step.

- ^ Helen Saunders, c.1915 Vorticist Design in the Tate collection.

- ^ Those listed as having been ‘invited to show’ were Bernard Adeney, Lawrence Atkinson, Bomberg, Duncan Grant, Jacob Kramer and Nevinson (labelled ‘Futurist’).

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p.25

- ^ For example, P. G. Konody in The Observer, 4 July 1915: ‘the “Vorticists” continue their antics in times as serious and critical as the present.’

- ^ Gaudier-Brzeska had enlisted in the French army – the Regimente d’Infanterie 129e – and was killed in the trenches of Neuville Saint-Vaast on 5 June 1915.

- ^ BLAST: War Number, published July 1915, p. 7.

- ^ Robert Hewison, ‘Blast and the Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in Antliff & Greene (eds.), The Vorticists, p. 71.

- ^ Jonathan Black, ‘Taking Heaven by Violence’, in Jonathan Black (ed.), Blasting the Future!: Vorticism in Britain 1910–1920 (London: Philip Wilson, 2004), p. 35, and Peppin, ‘Women That a Movement Forgot’, p. 32.

- ^ Vivien Greene, ‘Ezra Pound and John Quinn: The 1917 Penguin Club Exhibition’, in Antliff & Greene (eds.), The Vorticists, p.76.

- ^ 8 East 15th Street, New York City.

- ^ Greene, ‘Ezra Pound and John Quinn’, pp. 78, 81.

- ^ Greene, ‘Ezra Pound and John Quinn’, p. 81.

- ^ See William Roberts, Memories of the War to End War 1914–18 (London, 1974) for an account of life on the front line and the commissioning processes for war artists.

- ^ Richard Cork, ‘Wadsworth and the Woodcut’, in Jeremy Lewison (ed.), A Genius of Industrial England: Edward Wadsworth 1889–1949 (Bradford: Arkwright Arts Trust, 1990), p. 20.

- ^ The rejected Sappers at Work study is in the Tate Collection.

- ^ See David Cleall, 'The First German Gas Attack at Ypres', in William Roberts Society Newsletter, October 2014.

- ^ Wadsworth – Adelphi Gallery, March 1919; Lewis – 'Guns', Goupil Gallery, February 1919; Roberts – Chenil Gallery, November 1923; and Atkinson – 'Abstract Sculpture and Painting', Eldar Gallery, May 1921.

- ^ Group X exhibited at the Mansard Gallery in Heal's & Son, Tottenham Court Road, London, from 26 March to 24 April 1920.

- ^ Wyndham Lewis, 'Introduction', in Group X exhibition catalogue, 1920.

- ^ Athletes Exercising in a Gymnasium, The Wedding, The Auction Room and The Cockneys – see 'William Roberts: Catalogue raisonné' available at http://www.englishcubist.co.uk/catchron.html.

- ^ Andrew Gibbon Williams, William Roberts: An English Cubist (Aldershot: Lund Humphries, 2004), pp. 52–5.

- ^ Peppin, 'Women That a Movement Forgot', p. 32.

- ^ Greene, 'Ezra Pound and John Quinn', p. 81.

- ^ Cork, Vorticism and Its Allies, p. 26.

- ^ A letter of 15 November 1964 from Lilian Bomberg to William Lipke in the Tate Gallery archive explains that David Bomberg 'was very angry indeed and I think rightly so that he was included in the Wyndham Lewis Tate Gallery exhibition'.

- ^ See John Roberts, 'A Brief Discussion of the Vortex Pamphlets', which first appeared in William Roberts, Five Posthumous Essays and Other Writings (Valencia, 1990).

- ^ William Roberts, Some Early Abstract and Cubist Work (London, 1957) and William Roberts, 8 Cubist Designs (London, 1969).

- ^ 11 November–5 December 1969.

- ^ 27 March–2 June 1974.

- ^ The exhibition catalogue was subsequently supported by Richard Cork's two-volume history Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age (London : Gordon Fraser Gallery, 1976).

- ^ Estorick Gallery, London, 4 February–18 April 2004, and Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 7 May–25 July 2004.

- ^ Exhibition dates: Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, North Carolina, 30 September 2010–2 January 2011; Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 29 January–15 May 2011; and Tate Britain, 14 June–4 September 2011.

References

[edit]- Antcliffe, Mark, and Greene, Vivien (eds.), The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World (London: Tate Publishing, 2010)

- Black, Jonathan (ed.), Blasting the Future!: Vorticism in Britain 1910–1920 (London: Philip Wilson, 2004)

- Cork, Richard, Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age (two volumes) (London: Gordon Fraser Gallery and Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976)

- Cork, Richard, Vorticism and Its Allies (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1974)

- Haycock, David Boyd, A Crisis of Brilliance: Five Young British Artists and the Great War. (London: Old Street Publishing, 2009)

- Pound, Ezra., 'Vorticism', in Fortnightly Review 96, no. 573 (1914), pp. 461–71

External links

[edit]- Ezra Pound's 1914 Vorticism essay in the Fortnightly Review

- Ezra Pound, Vorticism

- Wyndham Lewis Portraits exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 3 July – 19 October 2008

- Tate glossary

- A review of the 2011 Vorticism exhibition at Tate Britain by Professor Andrew Thacker.

- An English Cubist: William Roberts 1895–1980