Queen Anne, Seattle

Queen Anne | |

|---|---|

Queen Anne Hill as seen from the Bainbridge ferry | |

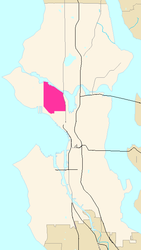

Map of Queen Anne's location in Seattle | |

| Coordinates: 47°38′14″N 122°21′25″W / 47.63722°N 122.35694°W | |

| Elevation | 120 m (394 ft) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1512589[1] |

Queen Anne is a neighborhood in northwestern Seattle, Washington. Queen Anne covers an area of 7.3 square kilometers (2.8 sq mi), and has a population of about 28,000. It is bordered by Belltown to the south, Lake Union to the east, the Lake Washington Ship Canal to the north and Interbay to the west.

The neighborhood is built on a hill, now named Queen Anne Hill, which became a popular spot for the city's early economic and cultural elite to build their mansions. Its name is derived from the Queen Anne architectural style in which many of the early homes were built.

Geography and history

[edit]Location and borders

[edit]

Queen Anne is bounded on the north by the Fremont Cut of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, beyond which is Fremont; on the west by 15th and Elliott Avenues West, beyond which is Interbay, Magnolia, and Elliott Bay; on the east by Lake Union and Aurora Avenue North, beyond which is Westlake. As a neighborhood toponym, Queen Anne may include Lower Queen Anne, also known as Uptown, the area at the southern base of the hill, just north and west of Seattle Center. Whether or not Lower Queen Anne is considered a separate neighborhood matters in setting Queen Anne's southern boundary, which is either West Mercer Street or Denny Way.[2]

Queen Anne can be reached from Interstate 5 via the Mercer Street Exit (Exit 167). The neighborhood's main thoroughfares are Gilman Drive West, 3rd Avenue West, Queen Anne Avenue North, Boston Street, and a set of streets, collectively known as Queen Anne Boulevard, that loop around the crown of the hill and reflect a comprehensive boulevard design in the style of the Olmsted Brothers architectural firm. The design was never fully executed, but it remains part of the Seattle Parks System.[3]

While Queen Anne stands out in Seattle geography due to its proximity to downtown and three television broadcast towers, the highest point in the city, 520 feet (160 m) above sea level, is in West Seattle. Queen Anne slopes are home to seven of the twenty steepest streets in the city[4] and 120 pedestrian staircases.[5]

Demographics

[edit]

Including the sub-neighborhoods of North Queen Anne, West Queen Anne, East Queen Anne and Lower Queen Anne (or Uptown), Queen Anne has approximately 19,000 households and a total population of about 36,000.[6] Queen Anne is disproportionately populated by unmarried, white, young adults. The population is more racially homogeneous than Seattle as a whole.

| Queen Anne[7] | Seattle[8] | United States[10] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population density | 5000/km2 | 2800/km2 | 39/km2 | 34/km2 |

| Male / female | 49% / 51% | 50% / 50% | 50% / 50% | 49% / 51% |

| Under age 18 | 9% | 15% | 24% | 24% |

| Over age 65 | 10% | 11% | 12% | 13% |

| Median age | 33.9 | 36.1 | 37.3 | 37.2 |

| Foreign born | 9% | 18% | 13% | 13% |

| White race | 83% | 70% | 77% | 78% |

| High school or higher | 98% | 92% | 90% | 85% |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 67% | 56% | 31% | 28% |

| Married | 37% | 40% | 52% | 50% |

| Average household size | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Renter / homeowner | 63% / 37% | 52% / 48% | 36% / 64% | 34% / 66% |

| Living in same house over 1-year | 70% | 77% | 82% | 85% |

| Median household income | $64,000 | $62,000 | $59,000 | $53,000 |

| Note: Education statistics are for population 25 years and older. Marital statistics are for population 15 years and older. All data are from 2010 census or American Community Survey. | ||||

Significant events

[edit]The Vashon Glacier carved Queen Anne Hill's topography more than 13,000 years ago, and human habitation in the area began some 3000 years ago. When white settlers arrived in the mid-19th century, the Duwamish tribe maintained a seasonal presence in and around Queen Anne.[11]

White settlement of Queen Anne stemmed from the arrival of the Denny Party at West Seattle's Alki Point in November 1851. In 1853, David Denny staked a claim to 320 acres (130 ha) of land the Duwamish called baba'kwoh, prairies, known today as Lower Queen Anne, and bounded by Elliott Bay to the west, Lake Union to the east, Mercer Street to the north, and Denny Way to the south. Denny called the area "Potlach Meadows". Development of the hill, called at various times North Seattle, Galer Hill, and Eden Hill, was slow. Then an 1875 windstorm flattened thousands of trees on Queen Anne, making the previously dense forest more appealing for settlement. The hill began to be called "Queen Anne" by 1885, after the Queen Anne style houses that dominated the area.[12] The arrival of the Northern Pacific Railway (1883) and the Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway (1887), the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, and the opening of three cable car lines to the top of the hill starting in 1890, including the Queen Anne Counterbalance, further encouraged residential and business development.[citation needed]

The 1917 opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, and the Fremont and Ballard Bridges over it, made the area more appealing for maritime and timber industries, and connected Queen Anne with communities to the north. On the south side of the hill, the 1927 completion of a Civic Center (with auditorium, ice arena and football field) on David Denny's Potlach Meadows land brought residents from all over the city to Queen Anne for concerts and sporting events.[citation needed]

The first television broadcast in the Pacific Northwest originated from the hill in November 1948, when KRSC-TV (now KING-TV) signed-on from its transmitting tower at Third Avenue North and Galer Street. KOMO-TV installed its own tower nearby, on Galer Street and Orange Place North, and began operations from there in December 1953, and KIRO-TV went on the air in February 1958 from a tower adjacent to its original studios on Queen Anne Avenue.[citation needed]

"The 1962 Seattle World's Fair was perhaps the most transformational single event in the history of Queen Anne", according to historians Florence K. Lentz and Mimi Sheridan. Named the Century 21 Exposition, the fair expanded on existing Civic Center infrastructure on the old baba'kwoh swale. After the fair, the grounds became the Seattle Center, home to the Space Needle, Pacific Science Center, Experience Music Project, Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame, the north terminal of the Seattle monorail and KeyArena.[13]

The Seattle SuperSonics began playing at the then-Seattle Center Coliseum in 1967. The Seattle Thunderbirds hockey team began play next door at the Mercer Street Arena in 1977. The Seattle Storm basketball team began play at KeyArena in 2000.[citation needed]

As late as 1964, the area had a large enough population of families with children to motivate opening McClure Middle School, but by 1981 a decline in such families led the school system to close Queen Anne High School, North Queen Anne Elementary School, and West Queen Anne Elementary School.[14]

Assistant United States Attorney Thomas C. Wales was shot in his home in the Queen Anne neighborhood on October 11, 2001, dying the next day of his wounds. The murder remains unsolved.[15][better source needed]

Landmarks

[edit]

Queen Anne is home to 29 official Seattle landmarks, including 12 historic houses. A group of residences on 14th Avenue West, built between 1890 and 1910, include one of the few remaining Queen Anne style houses on the hill.[16] The North Queen Anne Drive Bridge, built in 1936 across Wolf Creek, is a parabolic steel arch bridge, declared a historic landmark for its unique engineering style.[17] One of the oldest wooden-hulled tugboats still afloat, the Arthur Foss, is moored near the base of Queen Anne.[citation needed] Queen Anne Boulevard, which circles the crown of the hill, and some of the original retaining walls complete with decorative brickwork, balustrades, and street lights, are also designated landmarks.[18] Although not located at Queen Anne and no longer located west of present-day Seattle Center, the Denny Cabin was built by David Denny in 1889 as a real-estate office and was made from trees cut down on Queen Anne Hill.[19]

Community services

[edit]Businesses

[edit]

An 800 m (0.50 mi) stretch of Queen Anne Avenue North between West McGraw and West Galer Streets serves as the spine of the central business district. The Greater Queen Anne Chamber of Commerce is an association of neighborhood business leaders.[20] Queen Anne hosts a weekly farmers' market between June and October.[21]

News and information

[edit]The Queen Anne News is a weekly community newspaper founded in 1919 and published by the Pacific Publishing Company.[22] The Queen Anne View[23] is a neighborhood news blog.[better source needed]

Schools

[edit]Within the Seattle Public Schools district, Queen Anne is home to six public schools.

- Cascade Parent Partnership (currently operating near Greenlake while the Queen Anne building is renovated) [24]

- Frantz Coe Elementary

- John Hay Elementary

- Queen Anne Elementary

- McClure Middle School

- The Center School

Two former schools, Queen Anne High School and West Queen Anne School, are on the National Register of Historic Places. Both are now condominium apartment buildings.

Queen Anne has five private schools.

- Queen Anne Community School[25]

- St. Anne School

- Seattle Country Day School

- Seattle Waldorf High School

- The Downtown School, A Lakeside School

Queen Anne is served by Lincoln High School (Seattle, Washington) located in the Wallingford, Seattle neighborhood.[26]

Seattle Pacific University, a private university founded in 1891 by the Free Methodist Church of North America, has 4000 undergraduate and graduate students on a 43 acres (17 hectares) campus on the north slope of Queen Anne.[27]

Library

[edit]The Queen Anne branch of the Seattle Public Library is housed in a 1914 building funded by Andrew Carnegie and built in late Tudor Revival architecture style. The structure, renovated in 2007, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and has been named a landmark by Seattle's Landmarks Preservation Board.[28]

Parks and cemeteries

[edit]The Seattle Parks and Recreation department maintains 24 parks on Queen Anne. Kerry Park, located on Highland Drive, covers a mere 1.26 acres (0.51 ha), but boasts one of the most attractive views of the city, with downtown at the center of focus along with the Space Needle, and on clear days, Mount Rainier in the background. From this point there are also views of Elliott Bay and West Seattle.[29] Kinnear Park, with 14.1 acres (5.7 ha) of woodland and grass, is Queen Anne's largest park, offering views of the grain elevator at Pier 86.[30] Rachel's Park, formerly Soundview Terrace, is a play area on the west slope of the hill named after Rachel Pearson, a 6-year-old girl who died on Alaska Airlines Flight 261 in 2000.[31] Queen Anne Bowl, adjacent to the 9.2 David Rodgers Park on the north slope of Queen Anne, has a dirt running track and synthetic surface soccer pitch.[32] Bhy Kracke Park in East Queen Anne, features "one of the best views in the city," a playground, picnic shelter, several small grassy areas, and a paved walking path connecting the different levels of the park.[33] West Queen Anne Playfield includes a community center, indoor swimming pool, and baseball and softball fields.[34]

Queen Anne has two cemeteries: Mount Pleasant Cemetery and adjacent Hills of Eternity Cemetery, which is owned and operated by Temple De Hirsch Sinai.[35]

Government and infrastructure

[edit]Queen Anne Hill is part of Washington's 7th congressional district and 36th legislative district. Queen Anne residents are represented by Pramila Jayapal in the United States House of Representatives, Jeanne Kohl-Welles in the Washington State Senate, Reuven Carlyle and Mary Lou Dickerson in the Washington House of Representatives, and Larry Phillips on the Metropolitan King County Council.

Queen Anne has two ZIP codes: 98109 and 98119. The United States Postal Service operates the Queen Anne Post Office at 415 1st Avenue North.[36]

The Seattle Fire Department maintains two stations on Queen Anne.[37]

Notable people

[edit]

Past and present residents include:

- Sue Bird (1980–), former basketball player for the Seattle Storm, 4-time WNBA champion, 5-time Olympic Gold Medalist.[38]

- Alden J. Blethen (1845–1915), newspaper publisher.[39]

- Betty Bowen (1918–1977), journalist and art promoter; named "First Citizen of Seattle" two days before her death.[40]

- Arthur C. Brooks (1964–), social scientist and president of the American Enterprise Institute.

- Carlos Bulosan (1913–1956), Filipino-American novelist and poet.[41]

- Jack Clay (1926–2019), acting teacher, director and actor.

- George F. Cotterill (1865–1958), city engineer, state senator and mayor.[42]

- David Denny (1832–1903), Seattle co-founder.

- Robert E. Galer (1913–2005), marine corps aviator and medal of honor winner.[43]

- Hank Ketcham (1920–2001), cartoonist who created Dennis the Menace.[44]

- George Kinnear (1836–1912), real estate developer.[45]

- Jake Lamb (1990–), baseball player.

- Lawrence Denny Lindsley (1879–1974), photographer, miner, hunter and guide.

- Gary Locke (1950–), governor and cabinet secretary and former Ambassador to China.[46]

- Love Family (1940–), urban commune.

- Rick Parashar (1963–2014), record producer.

- Reginald Parsons (1873–1955), businessman and philanthropist.[47]

- Jonathan Raban (1942–2023), British travel writer and novelist.[48]

- Megan Rapinoe (1985–), soccer player for OL Reign, 2-time World Cup winner, Olympic Gold and bronze medalist.

- Gerard Schwarz (1947–), composer and conductor.[49]

- Edo Vanni (1918–2007), baseball player and manager.[50]

- Thomas C. Wales (1952–2001), federal prosecutor and gun control advocate gunned down in his Queen Anne Hill home.[51]

- Mike Webb (1955–2007), radio talk show host and activist.

- Rick White (1953–), member of U.S. House of Representatives.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Queen Anne

- ^ Seattle City Clerk's Neighborhood Map Atlas – Queen Anne. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Queen Anne Boulevard. Seattle Parks and Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Highest Elevations in Seattle. Seattle Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Dorpat, Paul. "Stair Struck". The Seattle Times. May 25, 2008.

- ^ Total Population and Households – King County Census Tracts 59/60/67/68/69/70/71 – U.S. Census website . United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ 98109 - Fact Sheet - U.S. Census website and 98119 - Fact Sheet - U.S. Census website . United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Seattle, Washington - QuickFacts Archived March 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Washington - QuickFacts Archived February 17, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ United States QuickFacts Archived April 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Wilma, David. Seattle Neighborhoods: Queen Anne Hill -- Thumbnail History. HistoryLink. June 28, 2001.

- ^ Hennes, John. Why Is Our Community Named Queen Anne? Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Queen Anne Historical Society, June 13, 2001.

- ^ Lentz, Florence K. and Mimi Sheridan, Queen Anne Historic Context Statement Archived June 7, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Prepared for the Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, Historic Preservation Program and the Queen Anne Historical Society, October 2005.

- ^ Reinartz, Kay (1993). Queen Anne: Community on the Hill. Queen Anne Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9638991-0-1.

- ^ Thomas C. Wales foundation.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: 14th Avenue W Residences (1890–1910). HistoryLink Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: Queen Anne Drive Bridge (1936). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: West Queen Anne Walls (1913). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ McDonald, Cathy (December 24, 2009). "History and a rare peat bog at West Hylebos Wetlands Park". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ Greater Queen Anne Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ Queen Anne Farmers Market.

- ^ Queen Anne News.

- ^ Queen Anne View.

- ^ "Cascade at John Marshall Building Through 2022-23 School Year". Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Queen Anne Community School". queenannecs.org. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Nile Thompson, Carolyn J. Marr, Nick Rousso (August 8, 2024). "Seattle Public Schools, 1862-2023: Lincoln High School". HistoryLink.org. Retrieved January 23, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ SPU Facts. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Seattle Public Library – Queen Anne Branch Archived December 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Seattle Public Library. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Kerry Park (Franklin Place). Seattle Parks and Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Kinnear Park. Seattle Parks and Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Denn, Rebekah. "A park from Rachel, with love". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Wednesday January 31, 2001.

- ^ Queen Anne Bowl Playfield. Seattle Parks and Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ "Bhy Kracke Park - Parks | seattle.gov". www.seattle.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- ^ West Queen Anne Playfield. Seattle Parks and Recreation. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Hills of Eternity Cemetery. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ QUEEN ANNE Post Office Location Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 5, 2009.

- ^ Seattle Fire Department Stations Archived June 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Seattle Fire Department. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Voepel, Michelle. "Ready To Let You In". ESPN. July 20, 2017.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: Ballard/Howe House (1901). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: Bowen Bungalow (1913). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ De Leon, Ferdinand M. (August 8, 1999). "Revisiting the life and legacy of a pioneering Filipino author". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: George F. Cotterill House (1910). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Wilma, David. Seattle Neighborhoods: Queen Anne Hill -- Thumbnail History. HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Rahner, Mark. "Dennis the deviant". The Seattle Times. October 9, 2005.

- ^ Wilma, Dave. Seattle Landmarks: Del a Mar Apartments (1909). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ "Locke seems likely choice for Commerce Secretary". Queen Anne View. February 24, 2009.

- ^ Wilma, David. Seattle Landmarks: Parsons House (1905). HistoryLink. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ^ Marshall, John. "Book Critics Laud Local Writer's 'Bad Land'", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 20, 2007. Accessed June 2, 2008.

- ^ Bond, Jeff. "Ending on a good note". Queen Anne News. September 14, 2010.

- ^ Stone, Larry. "Edo Vanni is the dean of Seattle baseball". The Seattle Times. February 13, 2005.

- ^ Miletich, Steve and Mike Carter. "Five years later, FBI still after Wales' killer". The Seattle Times. October 12, 2006.

External links

[edit]- Queen Anne Community Council

- Queen Anne Helpline

- Seattle Photograph Collection, Queen Anne – University of Washington Digital Collection

- "Queen Anne Hill". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved February 7, 2014.